M+B is pleased to announce Pulse, Didier William's first solo exhibition in Los Angeles and at the gallery. The show will be on view from September 23 to October 24, 2020. William draws on Haitian history, mythology and his personal experiences to explore the legacies of colonialism, resistance and the struggle for agency and identity. His powerful mixed media compositions lie halfway between figuration and abstraction. The epic, otherworldly bodies are composed of hundreds of tiny carved eyes that invite a haptic experience—an intimate, shared looking with the viewer that collapses physical and temporal planes.

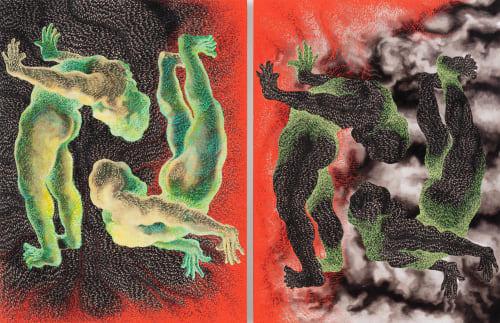

What is the meaning and role of the body in representing identity? Portraits—and traditional renderings of the body at work, at play, in battle, in repose—are classic and conventionally accessible means of conveying the moods and states of humanity. The forms in Pulse, Didier William's latest body of work, gesture towards a more boundless figuration. Though William borrows from the structure and scale of Romantic landscape painters like J. M. W. Turner and Alexander Cozens, he fully rejects the classical, hierarchical proportions of that era, where the bigness of God's nature necessarily dwarfs the comparatively featureless insignificance of human life, which is swallowed into the sublimity of the natural world. The Romantics painted during the French colonization of Haiti and during her revolution (1791-1804). The Napoleonic Wars and French Revolution, happening around the same time, were rendered visually; Haiti's struggle, by contrast, was rarely depicted by that class of artists. William's massive figures—a kind of canonical and ontological correction—inhabit the otherwise unoccupied and cavernous realm between the heavens and the earth; in the spirit of the world's first independent Black nation, these bodies, both familiar and fantastical, eschew exclusionary Enlightenment ideas about physical proportionality. They reflect, instead, the artist's contemplation of Black futurity.

William's latest figurative works are of titanic proportions. Dezabiye (2020), recalls Francisco de Goya's The Colossus (1808-12), and Manman an, petit fi a ak lesri sen an (2020) is a triplicate of poor Atlas condemned to hold the Earth on his shoulders. A proliferation of eyes, hewed into the paintings' wooden panels, characterizes William's work. These eyes are not simply returning a hostile and subjugating gaze. They are like apotropaic amulets warding off the evil eye: an army of ever-watchful, unblinking, cyclopean eyes. They are the materialization of an autonomous and collectivized claiming of the right to look.[i] Broadly monstrous in their physical forms, there is an unfixedness to the personalities and loyalties of these one-eyed mythological creatures. The cyclopean blacksmiths Arges, Steropes, and Brontes forged the thunderbolts that enabled Zeus to lead the Olympian gods to victory in the Titanomachy, the battle between the new generation of deities and the twelve children of the primordial gods Uranus (who ruled the heavens) and Gaia (whose domain was the earth). Homer's cyclops were savage man-eaters, uncivilized and anarchic: perhaps "bad," and certainly not the subservient craftsmen in Hesiod's divine genealogy. In the epic poem, Odysseus—who craftily introduces himself as Nobody—intoxicates the cyclops Polyphemus with wine before blinding him with a giant stake. "Nobody has blinded me!" he cries for help, the other cyclops leaving him to suffer alone at the hands of apparently divine punishment. Both homage and riposte to this mythology, William's eyes comprise a topography, a mapped storytelling and historicization of Black life. The bodies they surround, mark, and adorn are imbued with an intensity and unpredictability reminiscent of the prototypical Haitian battle for freedom and independence: a subjectivity with which whiteness is wholly unwilling to engage.

There is an illegibility to William's frequent use of Kreyòl-only titles, leading to characterizations of previous work as quintessential "'New World' production."[ii] The Kreyòl is as much a marker and negotiator of Haitian diasporic identity and expression as it is an affordance of in-group privacy. The opacity this privacy affords is the opposite of understanding via "grasping," a gesture of "enclosure if not appropriation," as Édouard Glissant puts it.[iii] We can interpret the figures' movements and interactions and postures, the theatricality narrating a story of tension and physicality—not unlike the drama of George Bellows' ring fighters. But, as a non-Kreyòl speaker, there is an ambiguity and exciting mystery to the game of visual interpretation without linguistic direction. "Liberté, égalité, opacité," goes William's motto of freedom dreams.

Pulse—the title of William's 2020 bicoastal exhibition, held at James Fuentes Gallery in New York, and M+B in Los Angeles—references the motif of hapticity, be it tender embrace or physical conflict. You can feel the pulse of someone's carotid artery by gently placing two fingers on the hollow of their neck, just beside the windpipe. You can hear someone's heartbeat/heart beat by putting your ear to their chest and listening to the organ's steady percussion. Intimacy is often most readily and viscerally understood through touch, but, in the time of this novel coronavirus pandemic (during which William completed this body of work), he compels us to consider how we communicate intimacy and closeness as we are forced to distance—when a freeness of touch has been (temporarily?) stolen from us. His work is animated by a sensory shift that juxtaposes our separations with figures that melt into one another and the spaces surrounding them, the borders that individuate them (and us) falling away.

With these giant figures collapsing the space between sky and earth and sea, William is also troubling the forward momentum of linear time. There is an element of surrealism to his figurative abstractions: the bodies he illustrates, the bodies of Black people, are disrupting and destabilizing space and time. Even in their muscularity, their mountainous steadfastness and strength, there is a delicacy and dreaminess to these images, as though we are looking at figures that are inhabiting some unearthly and ethereal plane: like a parallel universe or an afterlife. Some struggle and battle in the underworld, while others spend blissful eternity in the Elysian Fields. William's chromophilic embrace of vivid color invokes the idea of "the fall": a technicolored falling into (or from) states of grace or ecstasy, a heightened sensory perception reminiscent of psychedelic drugs made illegal despite their documented beneficial use as aids for introspection and psychological repair.[iv] Broadening our consciousness accordingly, then, the eyes are both ours and those of our ancestors; they are representative of a kind of an intimate, shared looking that collapses physical and temporal planes. We are looking at them and they are looking back at us, and we look at and alongside one another together, even if we cannot be physically together.

There is a baroque element to these works, an epic and grandiose inspiration of awe within the subjects he creates. Some forms are familiar, while others we must strain our eyes and interpretative abilities to understand. But there is no concern with this lack of familiarity. In the formations of new intimacies and reminders of old ones, William's images recall a question posed by Toni Morrison about the position and purpose of, and alienation from, strangers. She asks: "Why would we want to know a stranger when it is easier to estrange another?" Both William and Morrison question humanity, because, as Morrison puts it, "the concept of what it is to be human has altered."[v] This is especially so because blackened peoples are precluded from the category of the human as represented in its imperial form: take Leonardo da Vinci's L'uomo vitruvianoor The Vitruvian Man (1490), for example, a literal illustration of formal "perfection" and an ideological-aesthetic mold against which colonized peoples were forcibly contrasted. Morrison concludes by saying that there aren't really strangers, "only visions of ourselves, many of which we have not embraced, most of which we wish to protect ourselves from."[vi]

William's intervention is an invitation and a confrontation: it departs from the insistent and impossible attempt to assimilate Black people into the category of the human, and instead visualizes them/permits us to be as expansive as we want and need to be. If we cannot be "people," if forever precluded from humanity, then let us be giants—let us embrace the mythological and spiritual. Let our personhoods and cultural expressions, historiographies and relations, transcend the demarcations of what has been historically permitted; let us welcome the unfamiliar—the variety of possible outcomes—as we forge multidirectional futures and memories. Colors appear in space "as constellations [that] can be seen in any direction and at any speed."[vii] Black, as the hue-less color that subsumes all others and perfectly absorbs light; Black, as presented by William, is the beautiful multiplicity of material and metaphysical realities and existences.

Didier William (b. 1983, Port-au-prince Haiti) earned his BFA in painting from The Maryland Institute College of Art and an MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Yale University, School of Art. William's work was the subject of a 2020 solo exhibition at the Figge Art Museum, Davenport, IA. His work has also been exhibited at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT; Bronx Museum of Art, Museum of Latin American Art, Long Beach, CA; Museum at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia, PA; Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, AR; Museum of the African Diaspora; San Francisco, CA; James Fuentes, and Anna Zorina Gallery, both in New York. His work has received critical recognition from The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic, Harpers Magazine, New York Magazine, and Art In America. William was an artist in residence at the Marie Walsh Sharpe Art Foundation in Brooklyn, NY and has taught at several institutions including Yale School of Art, Vassar College, Columbia University, University of Pennsylvania and SUNY Purchase. He is currently Assistant Professor of Expanded Print at Rutgers University. Pulse is the artist's first solo in Los Angeles and with M+B. Didier William lives and works in Philadelphia.

For inquiries, please contact info@mbart.com.

[i] Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011).

[ii] Edouard Duval-Carrié, "Visuals of a 'New World'," in Didier William: Lakou (Davenport, Iowa: Figge Art Museum, 2020).

[iii] Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation, trans. Betsy Wing (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 192.

[iv] David Batchelor, Chromophobia (London: Reaktion Books, 2000).

[v] From Toni Morrison's essay "The Stranger," the introduction to David Bergman's 1998 photography monograph A Kind of Rapture. See David Bergman, A Kind of Rapture (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998), 3.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Josef Albers, Interaction of Color: 50th Anniversary Edition (4th Ed.) (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 39.